While many desk-shackled students may wish they were napping rather than enduring yet another monotonous lecture, learning is by no means confined within the classroom. In fact, we engage in focused learning activities every day. Think of the last time you ordered a book, booked a flight, or bought a car. How did you choose which book to read, where to go for vacation, or which car was best for you? You may have searched online, read reviews, or asked others for advice to help you make an informed decision. In a word, you learned.

Learning is a complex process with distinct stages, each with corresponding tasks and emotions. Understanding how users learn can help us design experiences that support the user throughout the entire process. So let’s learn a thing or two about learning itself.

A hierarchy of learning#section2

According to Benjamin Bloom’s landmark 1956 study, we can classify learning in a hierarchy of six levels, where each level forms the foundation for the next. At the base of Bloom’s Taxonomy lies knowledge and comprehension—the plain facts and figures we were quizzed on at school. Once the learner has knowledge and comprehends it, the learner can begin to apply her knowledge experientially as one might do when driving a car for first time. The highest levels of learning involve deeply analyzing ideas and combining them into something new—the realm of the expert.

Fig. 1: Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning.

Learning as a process#section3

While Bloom’s Taxonomy reveals the many levels of learning, understanding how these levels flow together in practice is crucial. Carol Kuhlthau, a professor at Rutgers University, studied how students researched topics for term paper assignments.. While roughly consistent with Bloom’s Taxonomy, her research yielded much greater insight into the sequential nature of learning and its implications on the digital environment. Let’s look at Carol’s key findings and see how we can apply them to design for learnability.

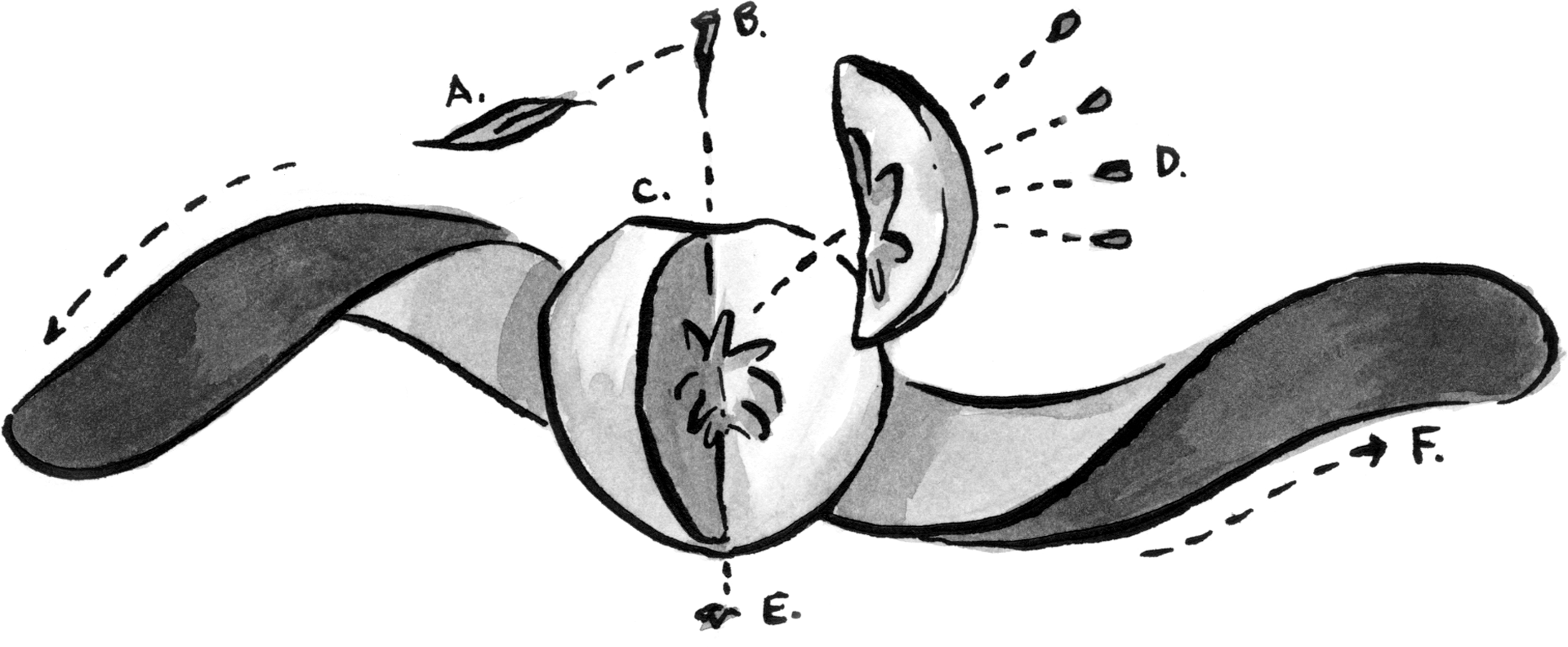

Fig. 2: A representation of the learning process from Carol Kuhlthau’s paper “Inside the Search Process.”

- Initiation

Initiation is the phase where you become aware that you need information. It’s often accompanied by uncertainty and apprehension. For example, my wife recently told me that she’s tired of taking the bus and wants a car. Hesitant at first, I eventually came around and agreed. Now I have a need to research vehicles.

-

Selection

The selection phase involves committing to constraints that narrow the information search. In our case, we quickly threw out motorcycles, vans, and SUVs, deciding to look only at small, family cars. This phase tends to produce a spike in optimism once the learner makes the selection.

-

Exploration

The optimism of selection usually gives way once more to confusion, uncertainty, and doubt as one realizes the many options still left to explore. Even though we had decided on small family cars, we still had to sift through dozens of makes and models, each with advantages and disadvantages. Kuhlthau’s study found that about half of her students never made it past this stage.

-

Formulation

Formulation is the turning point where all the information encountered thus far is formulated into a specific, tangible requirement. In our car hunt we reached formulation when we decided that a four-six-year-old five-door Nissan Almera hatchback with 30,000–50,000 miles was the best fit for our needs and budget. The formulation stage is marked by less anxiety and increased confidence.

-

Collection

Once the problem has been clearly articulated in the formulation phase, the next step is to evaluate the available solutions. Once we had a clear of idea of the model we wanted, we used automotive websites to search for cars in our area matching our criteria. Confidence continues to increase throughout the collection process.

-

Action

The final stage of the process is to perform an action based on the newly acquired knowledge. For Kuhlthau’s students, this meant actually writing the term paper. For me, it will mean going to the dealership, paying, and driving home a new car.

Designing for learnability#section4

Most websites invest the majority of their effort into streamlining the very last stage of this process: the action phase. It’s understandable: businesses make money through conversions. However, the company that best supports the user throughout the entire learning process has the upper hand in converting that loyal user into a paying customer. With that in mind, let’s look at digital solutions to seven learning-oriented tasks.

Explore#section5

“Unknown unknowns” characterize the beginning of the learning process. Often, users have no idea what’s out there. Rather than expect the user to search for a precise make and model at this point, we must help the user explore. Browsing and flexible filtering options can expose users to serendipitous discovery, while personalized suggestions can help users set off on the right foot.

Fig. 3: Last.fm keeps track of the music you listen to and recommends new artists based on how your musical tastes compare with others.

Fig. 4:TravelMatch.co.uk doesn’t force you to fill in a date or a destination like most travel websites. Instead, they help users explore holiday options by providing flexible filtering, such as the destination’s temperature.

Re-find#section6

Learning can be a long-term activity. Saving a page or item—whether in the browser, a shopping basket, or in a wish list—can help users return to something they found earlier. Showing a list of recently viewed items can also provide a more passive means for helping users re-find.

Fig. 5: Nutshell CRM shows a list of recently viewed items when the user focuses on the search box, but before they start typing.

Organize#section7

While simple bookmarking helps users re-find, a higher-level task is to actually understand the information encountered thus far and how it fits together. Often this simply occurs in the mind; other times we may jot ideas down on paper. Whatever the medium, organizing items and ideas into categories is key to the learning process.

Fig. 6: Foodily not only allow users to save their favorite recipes, but to organize them into meal plans.

Compare#section8

In addition to organizing items into categories, being able to view a side-by-side comparison aids in the analysis process, especially during the collection phase.

Fig. 7: Canon’s website allows users to compare up to three cameras side-by-side.

Annotate#section9

An extension of organize and compare, annotation enables users to enrich collected items with their own notes and ratings.

Fig. 8: Globrix allow users to rate and write notes on each property that they’ve bookmarked.

Monitor#section10

Toward the end of processing learning, the user typically has a decent understanding of what they want. And yet that ideal job, house, or car may still be elusive. The ability to save a search and receive an alert when something new appears can be priceless.

Fig. 9: Primelocation allows users to save a search, as well as to receive a daily email with any new properties matching the user’s criteria.

Collaborate#section11

We don’t often make decisions in a vacuum. Friends, colleagues, and spouses often get their say as well. Unfortunately, the collaborative learning process is very poorly supported on the web today. During my car search, my wife and I often sent links back and forth to one another through email, a less-than-perfect solution. Shared bookmarks and collaborative annotations and ratings would go a long way in making learning on the web more social.

Fig. 10: Google Bookmarks allows users to create lists of bookmarks, share those lists with others, and comment both on individual bookmarks, as well as on the list as a whole.

From the classroom to the computer screen#section12

Far from being monopolized by schools, learning is an essential human activity. Empathizing with and supporting users as they traverse the many stages of learning fosters happier users and a more profitable business. We could all benefit from psychologist Carl Rogers’s wise advice to educators:

A further element that establishes a climate for self-initiated experiential learning is emphatic understanding. When the teacher has the ability to understand the student’s reactions from the inside and has a sensitive awareness of the way the process of education and learning seems to the student, then again the likelihood of significant learning is increased.

Need to comment on the ubiquitous use of the term USER. Human beings who “use” are drug addicts. When referring to people who do things, just say “people.” It irks me tremendously that the sloppy writing allowed in the tech industry constantly dehumanizes people into “users.” People do things. Users are a society problem. If you want people, that is, fellow human beings, to connect with your application, your web site, then refer to them directly.

@indilynx — the term “user” is meant to differentiate from “viewers” like on television. It is not de-humanizing, it is actually quite the opposite. The fact that it means something else in the context of drugs and alcohol is quite irrelevant. “Users” are separate from designers, clients, and developers — in this context — even though all of the above are people.

@Tyler Tate — I have mixed feelings about this article. On the one hand your suggestions and examples for applying your lesson are quite good. The lesson of informing a user before prompting them to commit is a good lesson that many, many people — clients and designers alike — can use.

However…

I think the theoretical aspects of this article are a bit irresponsible. In a nutshell, you’re talking about facilitating “decision-making”, not learning.

Decision-making is the process of gathering information, forming an opinion and ultimately making a choice that leads to a desired result (those aren’t formal steps, for the record). Learning, on the other hand, is the process of gaining an understanding of a previously unknown subject, even as an end to itself, involving things like making information understandable, memorable, and progressive in presentation.

Half way through the article you even began to say “decision-making” rather than “learning”.

Learning may be likely in decision-making (although not necessary) but decision-making can be completely absent from learning.

I appreciate the article and the lesson, and I think there is some solid content in here. I think this article could use some editing though, to purify the separation between learning and decisions, because they appear in combination throughout the article.

Regardless of my opinions, thank you for the article.

@JMarsh I encourage this observation. There article is more about decision-making. That said, decision-support is a key function of mobile learning and therefore still relevant to learning.

As an educator & eLearning specialist, I want to emphasize the importance of sound pedagogy– bad instruction can do harm. For example, in language learning, poor instruction can lead students to “fossilize” (memorize) grammatical mistakes.

It’s great that ALA is addressing the learning issue. Just be careful not to over generalize. Good teaching takes as much skill and study as good design.

Learning is certainly intertwined with decision-making. This article is about user experience (person experience?)—and most of what people learn is by experience.

The experience you create for your users is just like any other experience one may have in life. Experiences can invite us, encourage us, and lead us to conclusions about what we want (or even what we believe in). But experiences can also intimidate and confuse us.

Very few important decisions (like ones involving money) are made without learning. And learning, whether by books, teachers, pixels, or the school of hard knocks, is always accompanied by an experience.

Experience truly is the best teacher. So as designers of experiences, making the connection between learning and decision-making is paramount.

Thank you for this article Tyler.

Thanks Tyler and ALA for helping usher in the awareness that our knowledge of learning needs to team up with our knowledge of design, for the benefit of both sides and the future of learning in a digital world.

I’ve been specializing in Learning Interface Design for about 10 years now and I still feel like a nube most days. It’s a sub-discipline with a past it can only borrow and a future in the making. As you point out in this article, knowing more about how people learn is important to good interface design, but it’s absolutely critical to Learning Interface Design (where the websites and technologies you create are dedicated specifically to an educational or training purpose.)

The research literature in Education and HCI indirectly produce nuggets of insight to inform design for learning, but oh the mountainous terrain of haystacks you have to machete through to get to these. I’m working on it. For anyone involved in Learning Interface Design, you might find something of interest at my blog or at the research community Mendeley where we’ve started a group in this area.

A very interesting post, to see the learning process broken down into the way we think. We all learn new things every day, come across new challenges, and the internet is definitely one of the main sources of our knowledge.

I think you have really grasped what we look for in a site when we are researching, which is the ability to compare, save and return to items of interest. All of these sites have great features and aspects that cover these important areas.

As much as the compare, bookmarking and annotation features that consumer sites are helpful, I think reviews are by far the best tool for people to research and make decisions. Personally, I don’t buy anything off Amazon that’s less than 4 stars, and even then I will read the worst reviews to try to determine if I might have a similar problem, or if the person was victim of an inevitable lemon.

The main issue is context. If I’m interested in a tent, for instance, I might be comparing two similar products. Maybe one is a pound or two lighter, which may seem like the better offer (all else being equal). However, if there are multiple reviews by actual people who have used the tent saying the lighter tent is awkward when folded making it difficult to carry (something the product specs couldn’t tell you) then I would steer the other direction. The real-world context provides more information than a 100 page spec sheet ever could.

Generally I think there is a pervasive level of suspicion when people are researching products, for instance, even if the site is credible. Is this medium the medium I’m used to? Does it actually fit in an overhead bin? Does the battery actually last eight hours? These questions can be answered credibly with reviews, alleviating the skepticism. But really anything we can do as designers/developers to connect users with real information is always helpful.

indilynx is simply quoting Jakob Nielsen.

A model should be developed for how a user can accurately detect false information, it’s a type of learning, but I think you would need to break the Compare step down further. For example, how do you spot fake reviews on Amazon.com? I have my own methods, I’m very interested to hear others.

First off, great article. With the intelligence level of ALA’s readership, it takes a brave person to submit an article.

I found your 6 steps of learning/decision-making an insightful look in to a user’s way of starting a project. And it reminded me of the Situational Leader diagram (i found a pdf of one here: theleadershipcollege.com, i’m sure there are other places). Both processes focus on a users’ confidence level.

For example, you noted 6 steps:

1 – Initiation uses “uncertainty”

2 – Selection uses “spike in confidence”

3 – Exploration goes back to “uncertainty”

4 – Formulation is another “increased confidence”

5 – Collection notes an increase in confidence

6 – Action

Now take Situational Leader – D1-D4:

D1 – enthusiastic beginner – low competence + high commitment

D2 – disillusioned learner – low to some competence + low commitment

D3 – capable but cautious performer – moderate to high competence + variable commitment

D4 – self-reliant achiever – High competence + high commitment

The two processes are not identical, but the similarities are evident. Both processes focus on the user’s confidence level as it correlates to their comprehension of newly acquired information.

I wonder if there are other related studies out there that focus on user confidence? Thanks Tyler, it’s great article to make you stop and think.

In regards to spotting bad or false reviews. I tend to cross examine reviews.

For example if you pick up a book on the subject of beginners PHP. There’s those who will say “This is the ultimate book” where others will say “The book is full of mistakes and doesn’t explain anything in detail”.

My solution? I’ll check it out for myself, look through the book, and make my own decision.

Great article! Thanks. There’s lots of very valuable issues covered. I just want to latch on to one big issue in this comment. Basically, the article theoretically describes learning as a discrete set of steps. Now, I think most people would say in practice the boundaries are fuzzy. But I want to go a step further in this comment and say that the vast range of learning styles (not to mention that people change learning styles frequently and even viewing can involve some learning) lead to problems when implementing steps. They help structure, but the steps may not always be in the right spacing to meet every learner’s intellectual gait. Over the years, I’ve come to adopt the scaffolding approach, which I’ve found is much more flexible in dealing with changing and evolving learning approaches. It’s less structured, but for one-on-one learning the scaffolding approach has greatly enhanced learning in my experiences.