Suddenly, I realized that the people next to me might be severely impacted by my work.

I was having a quick lunch in the airport. A group of flight attendants sat down at the table next to me and started to prepare for their flight. For a while now, our design team had been working on futuristic concepts for the operations control center of these flight attendants’ airline, pushing ourselves to come up with innovative solutions enabled by the newest technologies. As the control center deals with all activities around flying planes, our concepts touched upon everything and everyone within the airline.

How was I to know what the impact of my work would be on the lives of these flight attendants? And what about the lives of all the other people working at the airline?

Ideally, we would have talked to all the types of employees in the company and tested our concepts with them. But, of course, there was no budget (or time) allocated to do so, not to mention we faced the hurdle of convincing (internal) stakeholders of the need.

Not for the first time, I felt frustrated: practical, real-world constraints prevented me from assessing the impact and quality of my work. They prevented me from properly conducting ethical design.

What is ethical design?#section2

Right, good question. A very comprehensive definition of ethical design can be found at Encyclopedia.com:

Design ethics concerns moral behavior and responsible choices in the practice of design. It guides how designers work with clients, colleagues, and the end users of products, how they conduct the design process, how they determine the features of products, and how they assess the ethical significance or moral worth of the products that result from the activity of designing.

In other words, ethical design is about the “goodness”—in terms of benefit to individuals, society, and the world—of how we collaborate, how we practice our work, and what we create. There’s never a black-and-white answer for whether design is good or bad, yet there are a number of areas for designers to focus on when considering ethics.

Usability#section3

Nowadays usability has conquered a spot as a basic requirement for each interface; unusable products are considered design failures. And rightly so; we have a moral obligation as designers to create products that are intuitive, safe, and free from possibly life-threatening errors. We were all reminded of usability’s importance by last year’s accidental nuclear strike warning in Hawaii. What if, instead of a false-positive, the operator had broadcasted a false-negative?

Accessibility#section4

Like usability, inclusive design has become a standard item in the requirement list of many designers and companies. (I will never forget that time someone tried to use our website with a screen reader—and got absolutely stuck at the cookie message.) Accessible design benefits all, as it attempts to cover as many needs and capabilities as possible. Yet for each design project, there are still a lot of tricky questions to answer. Who gets to benefit from our solutions? Who is (un)intentionally left out? Who falls outside the “target customer segment”?

Privacy#section5

Another day, another Facebook privacy scandal. As we’re progressing into the Data Age, the topic of privacy has become almost synonymous with design ethics. There’s a reason why more and more people use DuckDuckGo as an alternative search engine to Google. Corporations have access to an abundance of personal information about consumers, and as designers we have the privilege—and responsibility—of using this information to shape products and services. We have to consider how much information is strictly necessary and how much people are willing to give up in exchange for services. And how can we make people aware of the potential risks without overloading them?

User involvement#section6

Overlapping largely with privacy, this focus area is about how we deal with our users and what we do with the data that we collect from them. IDEO has recently published The Little Book of Design Research Ethics, which provides a comprehensive overview of the core principles and guidelines we should follow when conducting design research.

Persuasion#section7

Ethics related to persuasion is about to what extent we may influence the behavior and thoughts of our users. It doesn’t take much to bring acceptable, “white hat” persuasion into gray or even dark territories. Conversion optimization, for example, can easily turn into “How do we squeeze out more revenue from our customers by turning their unconsciousness against them?” Prime examples include Netflix, which convinces us to watch, watch, and watch even more, and Booking.com, which barrages our senses with urgency and social pressure.

Focus#section8

The current digital landscape is addictive, distracting, and competing for attention. Designing for focus is about responsibly handling people’s most valuable resource: time. Our challenge is to limit everything that disrupts our users’ attention, lower the addictiveness of products, and create calmness. The Center for Humane Technology has started a useful list of resources for this purpose.

Sustainability#section9

What’s the impact of our work on the world’s environment, resources, and climate? Instead of continuously adding new features in the unrelenting scrum treadmill, how could we design for fewer? We’re in the position to create responsible digital solutions that enable sustainable consumer behavior and prevent overconsumption. For example, apps such as Optimiam and Too Good To Go allow people to order leftover food that would normally be thrashed. Or consider Mutum and Peerby, whose peer-to-peer platforms promote the sharing and reuse of owned products.

Society#section10

The Ledger of Harms of the Center for Human Technology is a work-in-progress collection of the negative impacts that digital technology has on society, including topics such as relationships, mental health, and democracy. Designers who are mindful of society consider the impact of their work on the global economy, communities, politics, and health.

Ethics as an inconvenience#section11

Ideally, in every design project, we should assess the potential impact in all of the above-mentioned areas and take steps to prevent harm. Yet there are many legitimate, understandable reasons why we often neglect to do so. It’s easy to have moral principles, yet in the real world, with the constraints that our daily life imposes upon us, it’s seldom easy to act according to those principles.

We might simply say it’s inconvenient at the moment. That there’s a lack of time or budget to consider all the ethical implications of our work. That there are many more pressing concerns that have priority right now. We might genuinely believe it’s just a small issue, something to consider later, perhaps. Mostly, we are simply unaware of the possible consequences of our work.

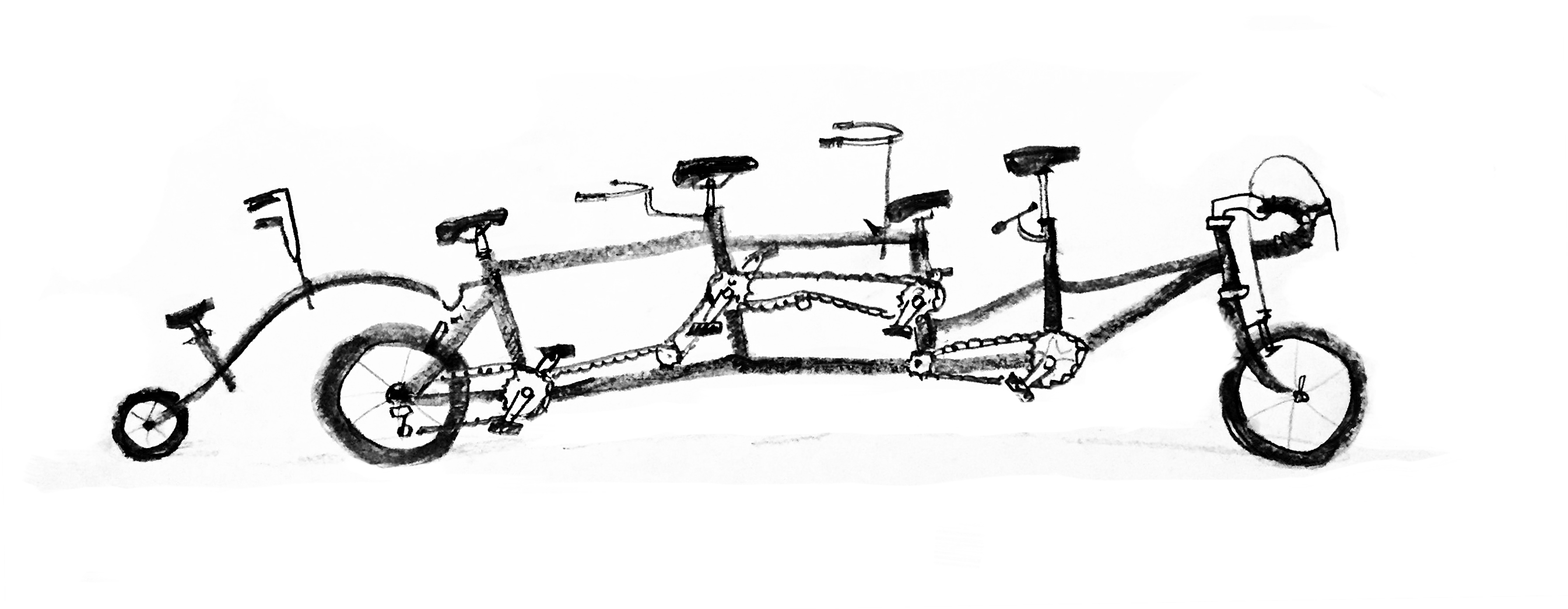

And then there’s the sheer complexity of it all: it’s simply too much to simultaneously focus on. When short on time, or in the heat of approaching deadlines and impatient stakeholders, how do you incorporate all of design ethics’ focus areas?

Where do you even start?

Ethics as a structural practice#section12

For these reasons, I believe we need to elevate design ethics to a more practical level. We need to find ways to make ethics not an afterthought, not something to be considered separately, but rather something that’s so ingrained in our process that not doing it means not doing design at all.

The only way to overcome the “inconvenience” of acting ethically is to practice daily ethical design: ethics structurally integrated in our daily work, processes, and tools as designers. No longer will we have to rely on the exceptions among us; those extremely principled who are brave enough to stand up against the system no matter what kind of pressure is put upon them. Because the system will be on our side.

By applying ethics daily and structurally in our design process, we’ll be able to identify and neutralize in a very early stage the potential for mistakes and misuse. We’ll increase the quality of our design and our practices simply because we’ll think things through more thoroughly, in a more conscious and structured manner.

But perhaps most important is that we’ll establish a new standard for design. A standard that we can sell to our clients as the way design should be done, with ethical design processes and deliverables already included. A standard that can be taught to design students so that the newest generation of designers doesn’t know any better than to apply ethics, always.

How to practice daily ethical design?#section13

At this point we’ve arrived at the question of how we can structurally integrate ethics into our design process. How do we make sure that our daily design decisions will result in a product that’s usable and accessible; protects people’s privacy, agency, and focus; and benefits both society and nature?

I want to share with you some best practices that I’ve identified so far, and how I’ve tried to apply them during a recent project at Mirabeau. The goal of the project was to build a web application that provides a shaver manufacturer’s factory workers insight into the real-time availability of production materials.

Connect to your organization’s mission and values#section14

By connecting our designs to the mission and values of the companies we work for, we can structurally use our design skills in a strategic manner, for moral purposes. We can challenge the company to truly live up to its promises and support it in carrying out its mission. This does, however, require you to be aware of the company’s values, and to compare these to your personal values.

As I had worked with our example client before, I knew it was a company that takes care of its employees and has a strong focus on creating a better world. During the kick-off phase, we used a strategy pyramid to structure the client’s mission and values, and to agree upon success factors for the project. We translated the company’s customer-facing brand guidelines to employee-focused design principles that maintained the essence of the organization.

Keep track of your assumptions#section15

Throughout our entire design process, we make assumptions for each decision that we take. By structurally keeping track of these assumptions, you’ll never forget about the limitations of your design and where the potential risks lie in terms of (harmful) impact on users, the project, the company, and society.

In our example project, we listed our assumptions about user goals, content, and functionalities for each page of the application. If we were not fully sure about the value for end users, or the accuracy of a user goal, we marked it as a value assumption. When we were unsure if data could be made available, we marked this as a data (feasibility) assumption. If we were not sure whether a feature would add to the manufacturer’s business, we marked it as a scope assumption. Every week, we tested our assumptions with end users and business stakeholders through user tests and sprint demos. Each design iteration led to new questions and assumptions to be tested the next week.

Aim to be proven wrong#section16

While our assumptions are the known unknowns, there are always unknown unknowns that we aren’t aware of but could be a huge risk for the quality and impact of our work. The only way we can identify these is by applying the scientific principle of falsifiability: seeking actively to be proven wrong. Only outsiders can point out to us what we miss as an individual or as a team.

In our weekly user tests, we included factory workers and stakeholders with different disciplines, from different departments, and working in different contexts, to identify the edge cases that could break our concept. On one occasion, this made us reconsider the entirety of our concept. Still, we could have done better: although scalability to other factories was an important success factor, we were unable to gather input from those other factories during the project. We felt our only option was to mention this as a risk (“limit to scalability”).

Use the power of checklists#section17

Let’s face it: we forget things. (Without scrolling up the page, can you name all the focus areas of design ethics?) This is where checklists help us out: they provide knowledge in the world, so that we don’t have to process it in our easily overwhelmed memory. Simple yet powerful, a checklist is an essential tool to practice daily ethical design.

In our example project, we used checklists to maintain an overview of questions and assumptions to user test, checking whether we included our design principles properly, and assessing whether we complied to the client’s values, design principles, and the agreed-upon success factors. In hindsight, we could also have taken a moment during the concept phase to go through the list of focus areas for design ethics, as well as have taken a more structural approach to check accessibility guidelines.

The main challenge for daily ethical design#section18

Most ethics focus areas are quite tangible, where design decisions have immediate, often visible effects. While certainly challenging in their own right, they’re relatively easy to integrate in our daily practice, especially for experienced designers.

Society and the environment, however, are more intangible topics; the effects of our work in these areas are distant and uncertain. I’m sure that when Airbnb was first conceived, the founders did not consider the magnitude of its disruptive impact on the housing market. The same goes for Instagram, as its role in creating demand for fast fashion must have been hard to foresee.

Hard, but not impossible. So how do we overcome this challenge and make the impact that we have on society and the environment more immediate, more daily?

Conduct Dark Reality sessions#section19

The ancient Greek philosopher Socrates used a series of questions to gradually uncover the invalidity of people’s beliefs. In a very similar way, we can uncover the assumptions and potential disastrous consequences of our concepts in a ‘Dark Reality’ session, a form of speculative design that focuses on stress-testing a concept with challenging questions.

We have to ask ourselves—or even better, somebody outside our team has to ask us— questions such as, “What is the lifespan of your product? What if the user base will be in the millions? What are the long-term effects on economy, society, and the environment? Who benefits from your design? Who loses? Who is excluded? And perhaps most importantly, how could your design be misused? (For more of these questions, Alan Cooper provided a great list in his keynote at Interaction 18.)

The back-and-forth Q&A of the Dark Reality session will help us consider and identify our concept’s weaknesses and potential consequences. As it is a team effort, it will spark discussion and uncover differences in team members’ ethical values. Moreover, the session will result in a list of questions and assumptions that can be tested with potential users and subject matter experts. In the project for the airline control center, it resulted in more consideration for the human role in automatization and how digital interfaces can continue to support human capabilities (instead of replacing them), and reflection on the role of airports in future society.

The dark reality session is best conducted during the convergent parts of the double diamond, as these are the design phases in which we narrow down to realistic ideas. It’s vital to have a questioner from outside the team with strong interviewing skills and who doesn’t easily accept an answer as sufficient. There are helpful tools available to help structure the session, such as the Tarot Cards of Tech and these ethical tools.

Take a step back to go forward#section20

As designers, we’re optimists by nature. We see the world as a set of problems that we can solve systematically and creatively if only we try hard enough. We intend well. However, merely having the intention to do good is not going to be enough. Our mindset comes with the pitfall of (dis)missing potential disastrous consequences, especially under pressure of daily constraints. That’s why we need to regularly, systematically take a step back and consider the future impact of our work. My hope is that the practical, structural mindset to ethics introduced in this article will help us agree on a higher standard for design.

No Comments

Got something to say?

We have turned off comments, but you can see what folks had to say before we did so.

More from ALA

To Ignite a Personalization Practice, Run this Prepersonalization Workshop

The Wax and the Wane of the Web

Opportunities for AI in Accessibility

I am a creative.

Humility: An Essential Value